Most snakes are more friend than foe

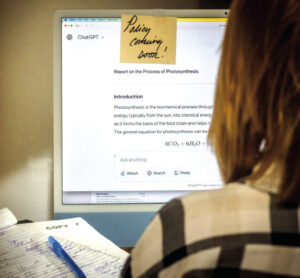

SPRUCE PINE — When naturalist Joel Pounders sees his four-year-old grandson, Koda McNutt, holding a smooth earth snake (harmless and fully grown at just a few inches), he’s glad he already knows it’s safe to do so.

The Spruce Pine resident and lifelong student of Alabama wildlife has spent decades teaching others that snakes, despite their reputation, are more often friend than foe. It’s a common mistake.

Alabama is home to about 40 snake species, but only six are venomous, and just four of those are typically found in Franklin County.

“The overwhelming majority are nonvenomous and beneficial,” Pounders said.

The venomous snakes include the timber rattlesnake, cottonmouth, copperhead, and the rarely seen pygmy rattlesnake. Coral snakes are extremely rare but can be found in the area, while eastern diamondbacks are not found in north Alabama.

In contrast, the king snake is one of the most welcome guests.

“They hunt copperheads and rattlers,” Pounders said of king snakes. “They’re immune to venom. I’ve got some living near my house, and they’re like family pets.”

Snakes like the gray rat snake are the most common snakes people ask him to identify or remove.

“Completely harmless,” he said. “But people still kill them.”

That’s one of his biggest concerns: That people are wiping out the helpful snakes while the venomous ones stay hidden.

“The harmless snakes are traveler types — they move around, so people see them,” he explained.

“But pit vipers? They sit still and wait. They’re ambush predators. So, people kill the ones they see and leave the ones they don’t. That’s a dangerous imbalance.”

Snakebites

Pounders said most snakebites occur when the weather is warm — typically above 75 degrees — and often at night.

“Most bites happen just after dark, especially in summer, with the highest risk between 8:30 p.m. and midnight,” he said.

He added that common myths about treatment — like sucking venom or using a tourniquet — can make the situation worse.

“Stay calm, identify the snake if you can, and get to the hospital as fast as possible,” he said.

Venom affects the body in different ways, depending on the species.

“Copperheads, cottonmouths and most rattlers are hemotoxic — their venom destroys tissue,” he said.

Coral snakes, on the other hand, are in a different category altogether.

“Coral snakes are neurotoxic, which affects the nervous system. Timber rattlers can have a little of both.”

“And for the record,” he said, “there’s no such thing as a poisonous snake.”

It’s a term he says gets thrown around a lot, but it’s not accurate because poison is ingested while venom is injected.

Misidentified snakes

What if you see a snake on the water? Odds are high it’s not a cottonmouth.

“Most water snakes are nonvenomous,” Pounders said. “We have a whole group of banded, plainbellied, midland, and green water snakes that people mistake for water moccasins.”

Other snakes frequently misidentified include the hog-nose snake, which Pounders says is known for its “dramatic bluff.”

“He’ll spread his head like a cobra and hiss like he’s going to strike,” Pounders said. “But he’s just putting on a show.”

The corn snake, with its vibrant orange and gray markings, is also harmless and often confused with more dangerous species.

And then there’s the black racer — Alabama’s speedster.

“He’s our fastest terrestrial snake. If you see one bolt through your yard, it’s probably him,” Pounders said.

Small, slender snakes like the ribbon snake, green snake and ringnecked snake are also frequently killed because of cases of mistaken identity.

“People think they’re babies, but most are fully grown,” he said.

Ecological benefits

Though not found in Franklin County, Alabama’s largest native snake, the indigo, can reach up to nine feet long.

“They’re gorgeous,” Pounders said. “And they’ve made a comeback in south Alabama thanks to university conservation efforts. It’s one of the good success stories.”

As a student at the University of North Alabama, Pounders experienced snake education firsthand.

“One of our assignments was to catch and identify every snake species in our region,” he said. “We studied them in the lab, then released them.” That kind of deep understanding shaped the way he sees snakes — not as threats, but as essential parts of the ecosystem.

“Snakes don’t just control rodents — they’re part of a delicate balance,” he said. “Snakes feed owls, hawks, eagles — even largemouth bass,” Pounders said.

Snakes play a vital role in keeping the population of disease-carrying rodents in check.

“They’re a key part of controlling diseasespreading pests,” he added. “Without snakes, rodent populations can explode — especially on farms.”

He recalls a late-night call from an 80-year-old woman who couldn’t sleep because of mysterious sounds in her attic.

“She said it sounded like something sliding across the rafters,” Pounders said.

He climbed up to investigate.

“I found a 74-inch gray rat snake. Totally harmless, just hunting mice and birds.”

He helped her seal up the attic and carried the snake out.

“Every time I see her, she hugs my neck and says, ‘Now I can sleep at night.’”

Teaching others

Pounders is passing respect down to the next generation.

His grandson already knows the difference between venomous and nonvenomous snakes — and how to react.

“If it’s harmless, he’ll hold it,” Pounders said. “If it’s not, he backs up and says, ‘Papa, venomous snake!’ He’s four and already knows the difference.”

Pounders said the attitudes children see in the adults around them are especially vital in shaping their outlooks into healthy ones.

“Most of the fear we pass on comes from how we act around children,” he added. “If we scream and panic, our kids learn to do the same. But if we teach them how to tell the difference, they grow up informed, not terrified.”